Shoulder Instability

What is shoulder instability?

Shoulder instability is a problem that occurs when the structures that surround the shoulder joint do not work to maintain the ball within its socket. If the joint is too loose, it may slide partially out of place, a condition called subluxation (partial dislocation of the shoulder joint). If the joint comes completely out of place, this is called a shoulder dislocation.

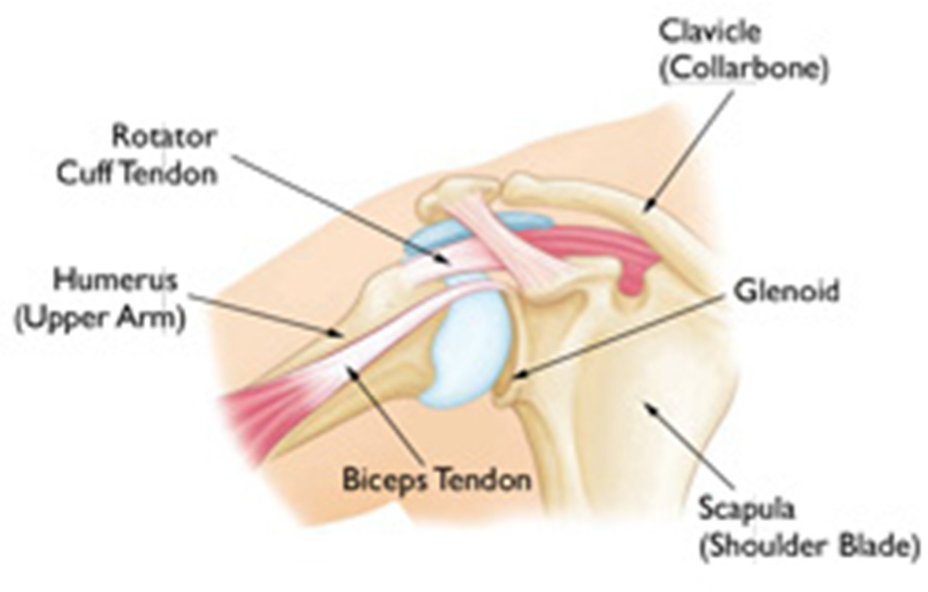

No single structure is responsible for providing stability at the shoulder joint. Instead, the bony structure of the joint surfaces, the ligaments, capsule and muscles are all key components in maintaining a stable shoulder joint yet permitting a large range of movement in several directions.

Instability is often associated with subluxation, which may be associated with pain and/or dead arm sensation. This is often what prompts the patient to seek medical attention. In some people, this is not actually painful but can be quite annoying and prevent them from taking part in daily activities or sports.

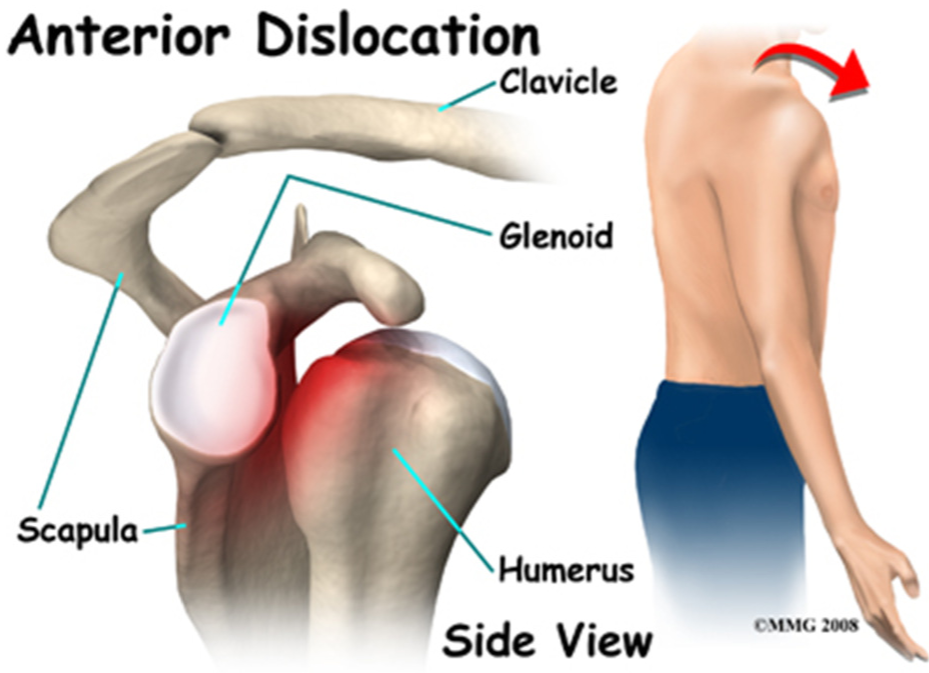

Instability of the shoulder joint can be in one direction, eg anterior instability (out the front), posterior instability (out the back) or in more than one direction (known as multidirectional instability). The most common form of instability seems to be anterior and is probably because the joint capsule is at its weakest at the front of the joint.

What causes an unstable shoulder?

The shoulder is the most moveable joint in your body. It helps you lift your arm, rotate it, and reach up over your head. It is able to turn in many directions. This greater range of motion, however, results in less stability. Shoulder instability occurs when the head of the upper arm bone in forced out of the shoulder socket. This can happen as a result of a sudden injury or from overuse.

Shoulder instability is most commonly caused by two different problems, placing people into two different categories in terms of treatment options. The category of “post-traumatic” shoulder instability includes people with a previous injury that has stretched or torn the ligaments of the shoulder. A second category is used for people who naturally have loose shoulder joints.

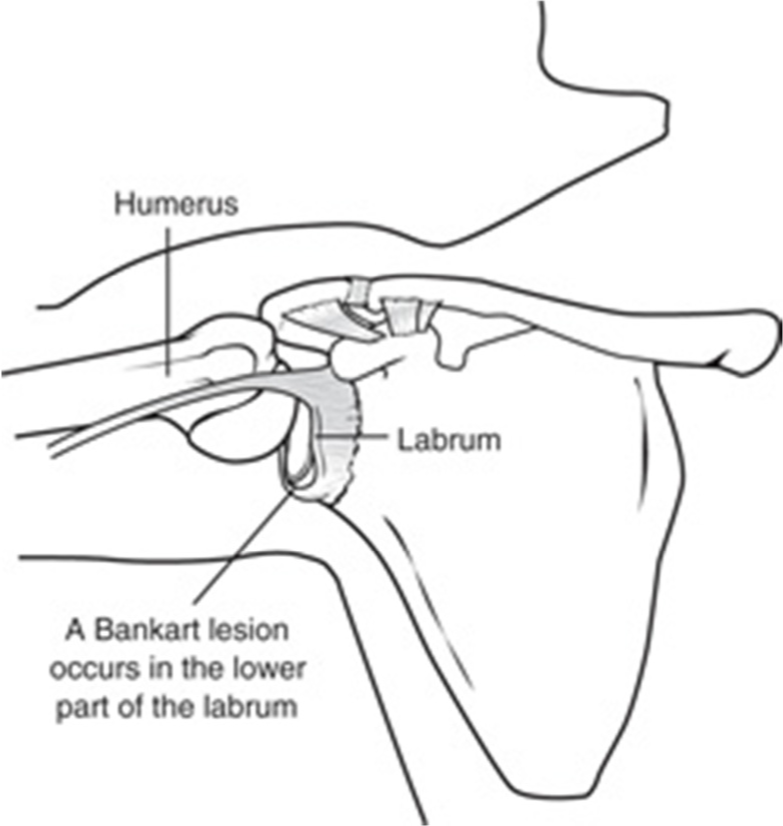

A bad injury to the shoulder can cause the shoulder to become unstable by stretching or tearing the ligaments of the shoulder away from the bone. When the ligaments of the shoulder are pulled away from the bone, this type of an injury is called a “Bankart lesion.”

Shoulder instability can also be caused by a generalized looseness of the joints, which is thought to represent some type of congenital ligamentous laxity. This means that certain people are born with ligaments that are more loose than normal. These people are frequently very flexible and are often called “double-jointed,” especially when they are school-age children. These people often have a shoulder that can slip out of joint in more than one direction, a condition that is called “multi-directional instability.”

The younger a patient is at the time first subluxation or dislocation episode, the more likely he or she is to suffer from further episodes of instability. Conversely, shoulder instability is less of a problem as people grow older, because most people naturally become a little bit stiffer with age.

Shoulder instability tends to occur in three groups of people:

- Prior Shoulder Dislocations –

Patients who have sustained a prior shoulder dislocation often develop chronic instability. In these patients, the ligaments that support the shoulder are torn when the dislocation occurs. If these ligaments heal too loosely, then the shoulder will be prone to repeat dislocation and episodes of instability. When younger patients (less than about 35 years old) sustain a traumatic dislocation, shoulder instability will follow in about 80% of patients. - Young Athletes – Athletes who compete in sports that involve overhead activities may have a loose shoulder or multidirectional instability (MDI). These athletes, such as volleyball players, swimmers, and baseball pitchers, stretch out the shoulder capsule and ligaments, and may develop chronic shoulder instability. While the joint may not be completely dislocated, the apprehension, or feeling of being about to dislocate, may interfere with their ability to play these sports.

- “Double-Jointed” Patients – Patients with some connective tissue disorders may have loose shoulder joints. In patients who have a condition that causes joint laxity, or double-jointedness, their joints may be too loose throughout their body. This can lead to shoulder instability and even dislocations

There are three common ways that a shoulder can become unstable:

Shoulder Dislocation

Severe injury, or trauma, is often the cause of an initial shoulder dislocation. When the head of the humerus dislocates, the socket bone (glenoid) and the ligaments in the front of the shoulder are often injured. The torn ligament in the front of the shoulder is commonly called a Bankart lesion. A severe first dislocation can lead to continued dislocations, giving out, or a feeling of instability. Dislocations can be posterior, inferior, superior or intra thoracic, although these are very rare

Repetitive Strain

Some people with shoulder instability have never had a dislocation. Most of these patients have looser ligaments in their shoulders. This increased looseness is sometimes just their normal anatomy. Sometimes, it is the result of repetitive overhead motion. Swimming, tennis, and volleyball are some sports examples of repetitive overhead motion that can stretch out the shoulder ligaments. Many jobs also require repetitive overhead work. Looser ligaments can make it hard to maintain shoulder stability. Repetitive or stressful activities can challenge a weakened shoulder. This can result in a painful, unstable shoulder.

Multidirectional Instability

In a small minority of patients, the shoulder can become unstable without a history of injury or repetitive strain. In such patients, the shoulder may feel loose or dislocate in multiple directions, meaning the ball may dislocate out the front, out the back, or out the bottom of the shoulder. This is called multidirectional instability. These patients have naturally loose ligaments throughout the body and may be “double-jointed”.

What symptoms should I look out for?

Common symptoms of chronic shoulder instability include:

- Pain caused by shoulder injury

- Repeated shoulder dislocations

- Repeated instances of the shoulder giving out

- A persistent sensation of the shoulder feeling loose, slipping in and out of the joint, or just “hanging there”

Many times, the athlete with instability will have a feeling that the shoulder wants to “come out of socket”. This is the shoulder slipping or sliding forward on the glenoid and into the labrum. Typically, the person will feel this “slipping” when they have the shoulder in what is known as the provocative position. This is the position that they would be in if the arm was cocked and ready to throw a ball. As the athlete continues to throw, the tear can increase and sooner rather than later, the athlete can no longer perform at their desired level. At this point, they will more than likely decide to have the shoulder repaired surgically.

Symptoms of a shoulder dislocation include:

- Sudden onset of severe pain in the shoulder

- If there is any nerve or blood vessel damage, there may also be pins and needles, numbness or

discolouration through the arm to the hand - Loss of shoulder function Ð difficulty and pain on trying to move the shoulder

- The shoulder will appear deformed, losing the smoother, rounded contour

- Swelling

Do not try to move the shoulder or put in back yourself, otherwise you may cause further damage. You must seek medical attention immediately.

What treatment options are available?

Treatment of shoulder instability depends on several factors, and almost always begins with non-surgical options. If patients complain of a feeling that their shoulder is loose or about to dislocate, physiotherapy with specific strengthening exercises will often help maintain the shoulder in proper position. Shoulder strengthening is most likely to help those patients with multi-directional instability. It often takes several months of non- surgical treatment before you can assess if it is working. Other treatments include cortisone injections and anti- inflammatory medications.

What are the surgical repair options?

If any of the above conservative treatment options fail, there are surgical options that can be considered depending on the cause of the instability.

- If the cause of the shoulder instability is a loose shoulder joint capsule, then a procedure to tighten the capsule of the shoulder may be considered.

- If the problem is due to a tearing of the ligaments around the shoulder, called the labrum, then a procedure called a Bankart repair can be performed to fix this ligament.

- The surgical operations that can be done in order to prevent shoulder dislocations are designed to repair and strengthen the ligaments that normally keep the shoulder in the joint.

How important is rehabilitation in the treatment of an unstable shoulder?

Rehabilitation plays a critical role in both the nonsurgical and surgical treatment of an unstable shoulder. There is frequently atrophy of the muscles around the arm and loss of motion of the shoulder, and an exercise or physiotherapy program is necessary to regain strength and improve function in the shoulder.

Immobilization

After surgery, therapy progresses in stages. At first, the repair needs to be protected while the shoulder heals. To keep your arm from moving, you will most likely use a sling and avoid using your arm for the first 4 to 6 weeks. Full healing takes 12 to16 weeks and occurs in 80-85% of patients who undergo surgery.

Passive Exercise

Once your surgeon decides it is safe for you to move your arm and shoulder, a physiotherapist will help you with passive exercises to improve range of motion in your shoulder. With passive exercise, your physiotherapist supports your arm and moves it in different positions. In most cases, passive exercise is begun within the first 4 to 6 weeks after surgery.

Active Exercise

After 4 to 6 weeks, you will progress to doing active exercises without the help of your physiotherapist. Moving your muscles on your own will gradually increase your strength and improve your arm control. At 12 to 16 weeks, you will usually start on a strengthening exercise program.

You can expect a complete recovery to take several months. Most patients have a functional range of motion and adequate strength by 6 to 9 months after surgery. Although it is a slow process, your commitment to rehabilitation is the key to a successful outcome.

What results can I expect after surgery?

The majority of patients report improved shoulder strength and less feelings of instability but your shoulder may never be NORMAL however.

Each surgical repair technique (open, mini-open, and arthroscopic) has similar results in terms of pain relief, improvement in strength and function, and patient satisfaction. Surgeon expertise is more important in achieving satisfactory results than the choice of technique.

Factors that can decrease the likelihood of a satisfactory result include:

- Poor tendon/tissue quality

- Large or massive tears

- Poor patient compliance with rehabilitation and restrictions after surgery

- Patient age (older than 65 years)

- Smoking and use of other nicotine products

- Workers’ compensation claims

What are some of the risks and complications of surgery?

After shoulder stabilisation surgery, a small percentage of patients experience complications. In addition to the risks of surgery in general, such as blood loss or problems related to anaesthesia, complications of surgery may include:

- Stiffness. Early rehabilitation lessens the likelihood of permanent stiffness or loss of motion. Most of the time, stiffness will improve with more aggressive therapy and exercise. If stiffness does occur, this may prolong your rehabilitation by an additional 6 to 12 months)

- Infection. Patients are given antibiotics during the procedure to lessen the risk for infection. If an infection develops, an additional surgery or prolonged antibiotic treatment may be needed.

- Nerve injury. This typically involves the nerve that activates your shoulder muscle (deltoid).

Be sure to follow the rehabilitation program that is provided for you. Although recovery is a slow process, your commitment to physiotherapy is the most important factor in returning to all the activities you enjoy.